Admiral Thomas C. Hart and the Asiatic Fleet (Final Days 1941-1942)

One of World War II’s early major American naval figures was Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander-inchief of the Asiatic Fleet, based in China and the Philippines. This is but a brief attempt to identify who he was and how he fit in to the awesome struggle that was played out in the final days before the loss of the Philippines and all of South East Asia to the Japanese in early 1942

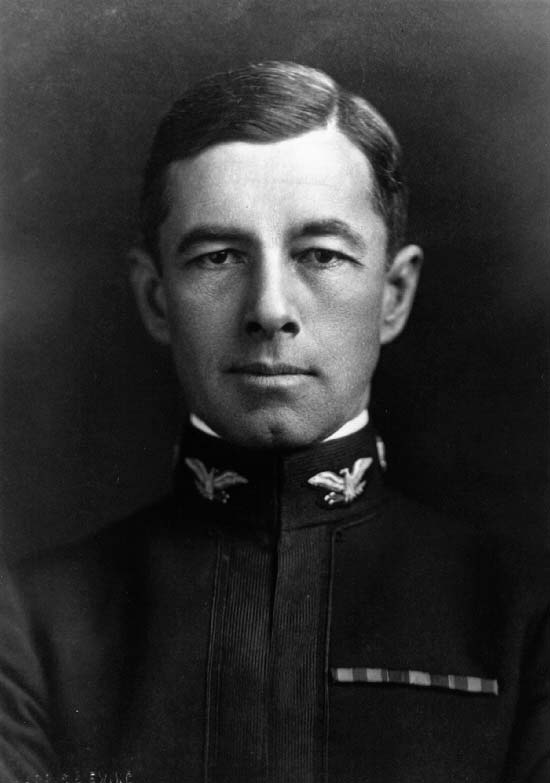

Thomas C. Hart, the last commander of the Asiatic Fleet, was born June 12, 1877, in Davison, Michigan. He died July 4, 1971, in Sharon, Connecticut, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In 1897 Thomas C. Hart graduated 13th in his class of 47 from the U.S. Naval Academy. His naval service in the Spanish American War and in World War I, and during the 1920s, included duty aboard destroyers, cruisers, battleships, and submarines and in the Navy Department, in a progression from midshipman to captain, and led to his selection to flag rank at the age of 52.

He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1929 and became first the commander of submarines in the Pacific based in Pearl Harbor, and then in 1930 he was the commander of the submarine base in Newport, Rhode Island. Then from 1931 through 1934 he was the Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy. He returned to sea in 1935 as the Commander Cruiser Scouting Force, United States Fleet, with the temporary rank of Vice Admiral which went along with that assignment. Ordinarily that would have been the apex of what surely was an illustrious naval career, there being only two rungs on the naval ladder any higher – that of the United States Fleet commander and that of the Chief of Naval Operations.

Appointed Commander Asiatic Fleet

In January 1937 Rear Admiral Hart, nearing his 60th birthday, was assigned to the General Board of the Navy Department, where other senior officers such as Rear Admiral Ernest J. King would also be serving in that advisory group to the Chief of Naval Operations. The General Board constituted a small pool of senior flag officers whose next move was usually retirement. However, for both Rear Admiral Hart, and for Rear Admiral King, that would prove not to be the case.

In July 1939 with Japan on a rampage in China, Rear Admiral Hart surprised his contemporaries and beat the odds by being picked by President Roosevelt for promotion to temporary four-star Admiral and assigned as the Commander of the U. S. Asiatic Fleet.

The Asiatic fleet commander’s mission in Asia was heavily laced with that of liaison with the British and the Dutch, a mission he shared with the U.S. High Commissioner of the Philippines, Francis B. Sayre, and one which necessitated an American of naval rank on an equal footing with that of his British and Dutch counterparts. The Commander of the Asiatic Fleet was the senior military service representative of the United States in the Far East.

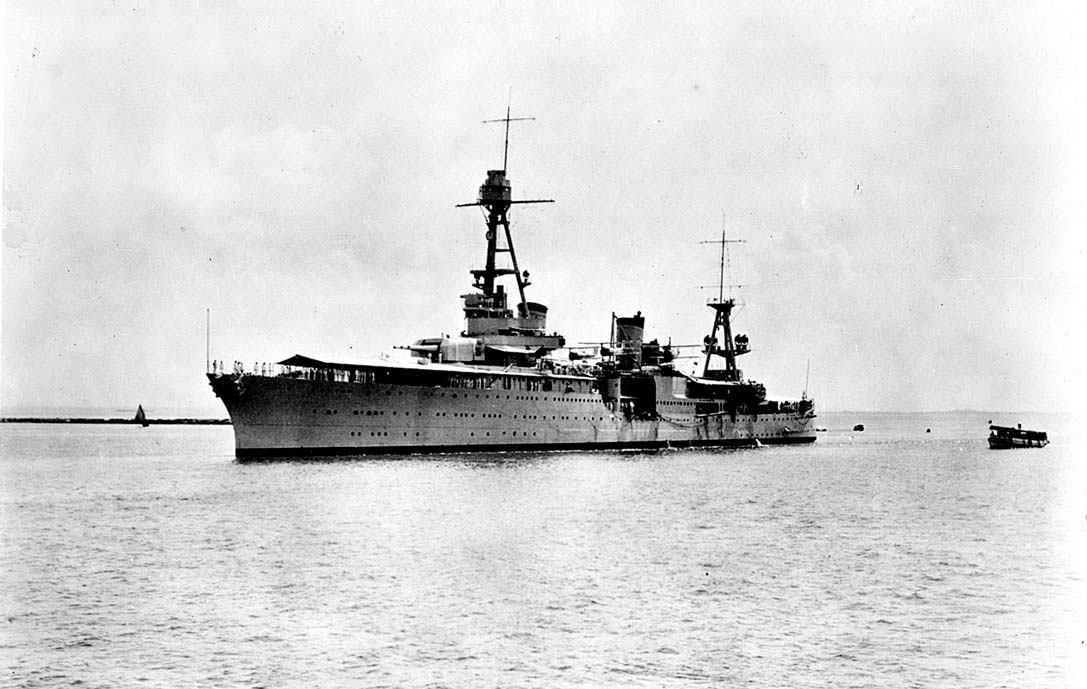

Admiral Hart relieved Admiral H. E. Yarnell aboard his flagship, cruiser USS Augusta on July 25, 1939.

In Manila retired U.S. Army Major General Douglas MacArthur, who held the rank of Field Marshal and Chief of Staff in the Commonwealth of the Philippines Army, had not as yet been called back to active duty as the American commander on the ground in the Philippines.

In the American hierarchy in the Philippines MacArthur occupied the number three position, after Admiral Hart and U.S. Major General George Grunert. Field Marshal MacArthur, the head of the Philippine Army in the Philippines -- but not the head of the American Army in the Philippines -- had to look to General Grunert, the commander of the small U.S. Army contingent on duty in the Philippines for his logistic needs in training the Philippine Army.

However, the American mission in the Far East required them all to work together, which history records that they surely did. Their objective was to stay the advance of Imperial Japan’s goal of conquering China, and down the road, Japan’s major objective of kicking out the Western nations and bringing all of the Far East under the Japanese banner.

Admiral Hart, in the summer of 1940-- after the fall of France and the Netherlands to the German Army, and with Japanese troops having moved in to the capital of French Indo-china -- relocated his headquarters ashore, moving into the Marsman Building in downtown Manila, and took up residence in the Manila Hotel, where MacArthur had his headquarters and occupied the hotel penthouse with his family. The concern now for the United States, and for Britain, and for the remnant of the Dutch government still functioning in the Dutch East Indies, was to determine what the Japanese would be doing next.

The cruiser USS Houston, under the command of Captain Albert H. Rooks, arrived in Manila in December 1940 to relieve the cruiser Augusta as flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. It appears likely that Captain Rooks brought his government’s latest detailed assessment and forecast concerning what could be expected of Japan, who was already beginning to build airfields in French Indo-china near the capitol of Saigon.

Japan, Germany, and Italy had entered into a mutual defense pact – the ―Tripartite Pact‖ – which meant that if Japan should start a war with the Western nations in the Far East, German and Italy were expected to jump in and help her. This both the United States and England knew because they were able to read the Japanese intelligence codes.

In January 1941 Admiral Hart ordered all naval wives and families to be evacuated from the Philippines and from the enclaves in Shanghai and other outposts in China.

Admiral Hart’s china-based ships would be making their way to the Philippines. But the U.S. Marines in China would remain there at their posts in Shanghai and other places, to protect American civilians until it was too late to get out, and all would be swept up in the firestorm which was only months away.

In early 1941 a major change in the alignment of the American navy took place. But the year before when Rear Admiral Ernest King was retrieved by President Roosevelt from the General Board it foreshadowed the event. From that point on Admiral King would be having an ever stronger impact on the future course taken by the American Navy in the war just around the corner. Admiral King would also be the decision-maker concerning the strategy for the Asiatic Fleet once the shooting began, as well as thereafter being the catalyst for change in the life of Admiral Hart.

In 1940 Rear Admiral King left the General Board of the Navy Department to become the Commander of the ―Combat Support Group‖ in the Atlantic – the name which for a short period was given to the American ships in that ocean, which had always been known as ―The Atlantic Squadron.

Then on February 1, 1941, the U.S. Atlantic Fleet was established, the Combat Support Group vanished from the organizational charts, and Rear Admiral King was promoted to four-star Admiral and Commander in Chief of the newly created U.S. Atlantic Fleet

At that same time the Navy also created the U.S. Pacific Fleet as an element of the United States Fleet, with Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel in Hawaii promoted to four-star admiral and the occupier of both entities as Commander in Chief. Admiral Kimmel’s jurisdiction on the organizational charts of this new "Two Ocean Navy" included in his chain-of-command the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, but in reality Admiral King’s instructions came out of Washington, not Hawaii. Admiral Hart and the Asiatic Fleet stood unaffected by those changes, but not by what would be taking place in the months ahead.

On July 26, 1941, Douglas MacArthur was recalled to active duty with the rank of Lieutenant General. The army of the Philippines was integrated into the United States Army. General MacArthur became the commanding general of the United States Army in the Philippines, with U.S. Army forces and the Philippine Army merged, all under his command. With MacArthur’s appointment, General Grunert was relieved by the Department of the Army and returned to the United States where he joined the Army Chief of Staff and became General George C. Marshall’s principal advisor concerning the Philippines.

For Admiral Hart, the change meant that his direct Navy-Army command relationship was now with General MacArthur.

For both Admiral Hart and General MacArthur, a war with Japan had become an almost certainty. On the same day that MacArthur was recalled to active duty, President Roosevelt had frozen all Japanese assets in the United States.

The next month, in August 1941 Admiral King in his flagship USS Augusta had the honor of transporting President Roosevelt and the presidential staff to Argentia Bay, Newfoundland, for Roosevelt’s historic meeting with Winston Churchill, which resulted in the "Atlantic Charter."

Meanwhile the German army continued its relentless march across Europe, sweeping up every country except Russia in its path, and was on the verge of invading England; and the United States remained deadlocked in a discussion with Japan, which if the issues remained unresolved was going to quickly bring on a show-down with Japan in the Pacific.

In that summer of 1941, with Admiral Hart headquartered ashore, it was Rear Admiral William. A. Glassford in the cruiser USS Marblehead who was generally the Senior Officer Present Afloat (SOPA). Admiral Hart’s flagship and other heavier units of the Asiatic Fleet were by then operating out of the harbor at Cavite, some seventy-five miles to the westward where fleet facilities were located at the naval base.

Meanwhile, after General MacArthur’s recall and the President’s historic meeting with the British Prime Minister in Argentia Bay, there was an about-face attempt by Washington to reinforce the Philippines, with the idea that there was still time to get that done before Japan launched an attack somewhere in Southeast Asia. B-17s were flown in to Clark Field. U.S. troops – mostly recently called-up National Guard units and other new Army recruits being rushed through basic training -- were readied for deployment to the Philippines. The British would be sending two of its mightiest warships, one the new Prince of Wales which had hosted the meetings of Churchill and Roosevelt in Argentia Bay, out to join the English fleet at Singapore.

In mid November the USS Portland, one of Admiral Kimmel’s cruisers in Pearl Harbor, escorted the Army Troop Transport Liberty to Manila, where 5,000 American infantrymen were unloaded. It would be the last of the reinforcements to reach the Philippines.

Admiral Hart and Commissioner Sayre went aboard the cruiser to look it over and visit with the ship’s captain. Its mission completed, the cruiser then left Manila.

December 8, 1941: A Day of Infamy

Portland was no sooner back in Hawaiian waters than the unthinkable happened—the Japanese fleet attacked Pearl Harbor.

The battleship backbone of the American fleet was broken. Pearl Harbor and the airfields and other military installations on Oahu were badly hit. Casualties were in the thousands. Nothing like it had ever happened before on American soil.

Quickly singled out by Washington leaders to blame for the magnitude of the Pearl Harbor disaster were the service chiefs in Hawaii; and Admiral Kimmel was relieved of his command on December 18. Named as the new Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet was Rear Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and Admiral King was named as the new Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, with him moved to Washington where a few weeks later he also was named as the new Chief of Naval Operations replacing Admiral Stark.

A few hours after the Pearl Harbor attack the first Japanese bombers appeared in the air over Clark Field, a short distance from Manila, and began their run on General MacArthur’s parked B-17s lined up below.

Admiral Hart, just days before, had ordered his surface ships to deploy southward, leaving little left at Cavite, where Japanese planes also struck but caused only minimum damage and casualties.

However, for the Philippines, unlike Hawaii, the worst was yet to come, and it would be served up piecemeal, while America’s attention was yet riveted on what had happened in Hawaii.

With Luzon soon invaded and all American positions being overrun and no relief or assistance in sight, in February President Roosevelt ordered General MacArthur to withdraw from the scene, so MacArthur, Mrs. MacArthur, their son, their maid, and the President of the Philippines were evacuated from Corregidor by a Navy torpedo boat and then to Australia in one of Admiral Hart’s submarines.

Then Admiral Hart a few days later also withdrew to the Dutch East Indies by submarine as he had been ordered to do. Had either the General or the Admiral stayed on, and had they been captured, it would have been a propaganda victory for the Japanese, not to mention that the United States would have run the risk of the enemy learning its intelligence codes had been broken and were being monitored. For that latter reason all of the ―code breakers‖ were also evacuated from the Philippines (and as they would be from the Dutch East Indies) before the arrival on the scene of the Japanese Army.

The American and the Philippine Army defenders under Major General Jonathan Wainright, who then became the commanding general, and Major General Edward P. King, Jr. his deputy on Luzon, had to all be left to their fate and make the surrender. Also on hand to meet the conquerors was High Commissioner Sayre, who would be later included in the exchange of American diplomats held by Japan for Japanese diplomats held in the United States.

Landing in Australia, General MacArthur vowed that he would return with a mighty army and drive the Japanese into the sea, and one-day three years later, with a big assist from the American Navy, he did return, and he did make good on that promise.

The ABDAFLOAT Command

In Batavia, Admiral Hart was placed in command of the ABDAFOAT warships, as a subordinate command of British General Sir Archibald P. Wavell, who had been named as the supreme commander of all Allied forces engaged in the defense of the Dutch East Indies,In the naval actions which then followed, the ABDA force took heavy losses, including damage to the cruisers Marblehead, which had to be withdrawn, and to Houston, which after hasty repairs in Australia, returned to the battle zone, where very soon she would be ending her days.

With the loss of the Dutch East Indies a certainty – as it was with the British East Indies – it appeared to the Allied governments that the fate of the Netherlands empire in the Far East should best rest in the hands of a Netherlands commander. In February Conrad E. L. Helfrich, Royal Netherlands Navy, replaced General Wavell as the supreme allied commander of the ABDA forces in the Indies; and the Dutch rear admiral, Karel W. F. Doorman was named to replace Admiral Hart as commander of the ABDA warships.

Admiral Hart was ordered by Admiral King (meaning of course, President Roosevelt) to disband the Asiatic Fleet and to return to the United States. Rear Admiral Glassford was ordered ashore, promoted to Vice Admiral and designated as the Commander U.S. Naval Forces Southwest Pacific.

Asiatic Fleet Disbanded

On February 15, The Asiatic Fleet was thus disbanded as an operating naval organization. Admiral Hart was flown out to Australia, from where he then returned to the United States for re-assignment.

Count-down to the End

After quick repairs in Brisbane, Captain Rooks -- now the American Navy’s senior officer at sea -- returned Houston to Java, where she was one of the heavy ships now assigned to Admiral Doorman.

In the ensuing Battle of the Java Sea on February 27- 28 it was a "ghastly defeat" for the ABDA warships, in which two cruisers were lost, two cruisers were damaged, including Houston, and three destroyers were sunk, with very little damage to the enemy. Among the ships lost was the Dutch cruiser DeRuyter, with most of those aboard, including Admiral Doorman. The saving of the Dutch East Indies had suddenly turned hopeless. The remaining ABDA warships were instructed to withdraw from the area. Coming down from the north was a vast armada of Japanese warships: battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, and transports loaded with thousands of troops.

Admiral Glassford, in Bandang with Admiral Helfrich, ordered Houston to accompany Perth, the remaining Australian cruiser, in a dash through Sunda Strait, to report to Tjlatjap, on Java’s southern shore, where the Dutch Admiral intended to gather his remaining ships for one last stand.

The two ships got underway, but in Sunda Strait on March 1, they met the enemy. Sunda Strait was heavily blockaded by Japanese warships. After a heated exchange of salvoes, and torpedoes fired by the Japanese ships, both Houston and Perth went down in a blaze of glory, and their captains and most of their crews with them.

In the meantime, on that same day Vice Admiral Glassford and his staff were air evacuated out of Java to Australia just hours before Japanese infantrymen stormed the airfield.

Admiral Glassford was also then flown home to the United States, where two months later he was the guest of honor at a special Memorial Day Ceremony in downtown Houston which marked the occasion of the swearing in of a thousand young Americans who had volunteered to replace the lost crew of the Houston. Some of the new recruits would be serving on another ship of that name soon to be launched. Admiral Glassford later in the year would be a liaison representative to the French government in exile, in the Allied campaign in North Africa, the beginning of the Second Front on the European continent.

A Last Navy Assignment

Admiral Hart, in returning to Washington, was again assigned to the Navy’s General Board. Then in July 1942 he was placed on the retired list, only to then be recalled to active duty the next month, again on the General Board, where he and a few others of flag rank continued to constitute a pool of senior officers to serve the needs of the war.

In January 1944 Admiral Hart was selected by the Secretary of the Navy to conduct a field inquiry into the Pearl Harbor disaster. He traveled into the Pacific to question witnesses and to gather testimony.

Admiral Hart himself of course was a walking encyclopedia of the events that had taken place in the Far East during the time he was there. It had been his naval intelligence unit housed in Cavite that had one of the keys to Magic and he had been passing that information to General MacArthur and to Washington. In Hawaii Admiral Kimmel had not possessed Magic, and Washington had kept Magic’s contents from him.

In 1944 a war was still going on, the very invasion of Japan in the planning. It would seem that the Navy did not know quite what to do with Admiral Hart. In any case, the story of the Asiatic Fleet and Admiral Hart’s role in the Far East had yet to be told, many of the details wrapped in tightest secrecy until well after the war, and others then being unknown or unclear to the Navy and to him, including the fate of the many crewmen of the old Asiatic Fleet who were no longer answering muster call.

As a United States Senator

In February 1945 Admiral Hart said his goodbyes to the General Board and retired from active naval service, having been asked by Governor Raymond E. Baldwin of Connecticut to fill the vacant Senate seat caused by the death in January of Senator Francis T. Maloney.

Admiral Hart, retired after more than fifty years of naval service, was sworn in as the new Republican Senator from the State of Connecticut on February 15, 1945.

Thus Hart’s mixed naval and naval diplomat career took on a new turn, one in which he would be a U.S. Senator when President Roosevelt died two months later and Vice President Harry Truman succeeded Roosevelt in office.

The war on all fronts still raged, but Germany would surrender in May. Japan would fight on until the obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and America would not need to invade Japan’s homeland shores.

In late 1945 the U.S. Congress began an investigation of the Pearl Harbor Disaster. It would go on well into l946.

One of the documents Congress would have to peruse was The Admiral Hart Inquiry, which Hart had conducted from February 12 through June 15, of 1944. Senator Hart would be one of the witnesses called before the committee to offer comments about his report and in further elaboration about his days of being the last Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet.

Sang Harbor

Old navy hands call it settling down in ―Snug Harbor‖, which indeed, retirement can be, if all has gone well and one has not fallen down too many ladders or slipped on too many wet decks.

After the war and at the end of his appointed Senate term, Senator Hart did not seek election. He settled in Sharon, Connecticut on the family’s farm, where for the next twenty-five years he lived in quiet seclusion as an honored and much respected retired four-star admiral of the United States Navy.

On Independence Day, July 4, 1971 Admiral Hart passed away at the age of 94.