Japan’s Planned Invasion of Australia in 1942, Rebuffed by the U.S. Offensive at Guadalcanal

Just to review this question for my own benefit, I having no doubt that Australia was being threatened by an invasion by Japan during the early stages of World War II, and that the threat was still very much alive and part of the U.S. strategic decisions meant to prevent such an event from occurring. The launching of the Guadalcanal Campaign and the struggle for an airfield that went on there was to that end, as well as to establish a base from which to move on up the island chain towards Japan. But I too would have trouble in recording that ―the next logical invasion was Australia‖ as wordage for Plaque # 2, and would suggest that a closer look be made of that sentence to make it less emphatic.

Back in 1942 there seems to have been no question that Australia, when and if Japan could get to it, would have been a target for Japan’s further attention. Japan in early 1942 had been intent on cutting off U.S. communication lines with Australia, with Australia and New Zealand thought to be on her list for invasion when the time was appropriate. Certainly that possibility was one of the major concerns for the Allied strategists having to deal with the war in the Pacific.

Some indication that Japan had in fact been leaning in that direction can be found in Brig. Gen. Samuel Griffith’s book, published in 1963, The Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 37. In his account of the Japanese Navy’s thinking in March 1942, from Japanese records and interviews available long after the war, which he cites, Griffith says, ―Navy [Japanese] planners now exploded another bombshell. This was no less a proposal to invade Australia.‖ Griffith goes on to say that the Japanese Army called the proposal ―ridiculous‖ and ―reckless.‖ None of that information, of course, was known back in 1942 when the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff was rushing to plug the holes in allied defenses in the Pacific. One can wonder if in some bottom drawer there had not been tucked away that ―reckless ‖ Japanese Navy plan. Or did Admiral Yamamoto’s war planners just chuck the whole thing in the nearest burn file.

In my own short monograph titled The Callaghan-Scott Legacy, written and published in 2002, and earlier in other writings, I have referred to ―the Solomon Islands . . .as being looked upon by the Japanese as being critically needed stepping stones for an invasion of Australia . . . and at Guadalcanal Japan had to be stopped.‖ In my mind, in the context of the times at Guadalcanal that statement stands as a perception of one of the realities of that campaign, and a driving force in the American resolve to see that the offensive at Guadalcanal was going to succeed come hell or high water.

Many writings at the highest political and military level pointed in that direction. Morison in his Volume 5, The Struggle for Guadalcanal, on page 12, states that Admiral King ―as early as February 1942 . . . .wanted Tulagi partly as an additional bastion to the American-Australian lifeline, partly as the starting point for a drive up the line of the Solomons into Rabaul, and as a deterrent to any further expansion by the Japanese.‖ In the next reference below, that ―further expansion‖ in the context of the worries of the ―highest political and military authorities of the United States and Great Britain‖ is clearly spelled out in the following:

In Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, by Army historian John Miller, Jr. [and the whole Department of the Army Historical Division] published by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1949 [Barnes and Noble Reprint, 1995], in Chapter 1- The Strategic Decision, on pages 1 & 2, we find the following:

"The decision [by the United States] to mount a limited offensive in the Pacific was a logical corollary to earlier strategic decisions. The highest political and military authorities of the United States and Great Britain had decided to defeat Germany before concentrating on Japan. . . . For the time being, Allied strategy in the pacific was to be limited to containing the Japanese with the forces then committed or allotted. Concentration against Germany, it was believed, would give the most effective support to the Soviet Union and keep the forces in the British Isles from being inactive, while containment of the Japanese would save Australia and New Zealand from enemy conquest. ‖ The two dominions, important to the Allies as sources of supply, as essential economic and political units of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and in the future to become bases for offensive operations, would have to be held. The implications of this decision were clear. If Australia and New Zealand were to be held, then the line of communications from the United States to those dominions would have to be held. Forces to defend the Allied bases along the line, including New Caledonia, the Fijis, and Samoa, had already [some, just before the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, and some, at the same time as in June the Battle of Midway raged] been sent overseas. There were not enough ships, troops, weapons, or supplies, however, to develop each base into an impregnable fortress. The bases were designed to be mutually supporting, and each island had been allocated forces sufficient to hold off an attacking enemy long enough to permit air and naval striking forces to reach the threatened position from adjacent bases, including the Hawaiian Islands and Australia. ‖ [italics added] [words in brackets added] --Three sources are cited in footnotes: ― JCS 23, Strategic Deployment of Land, Sea, and Air Forces of the United States, 14 Mar. 42; JCS Minutes, 6th Meeting, 16 Mar. 42; and JPS 21/7, Defense Island Bases along the Line of Communications between Hawaii and Australia, 18 April 42. (JCS 48 has the same title.)"

I don’t mean to say it necessarily follows that Australia and New Zealand were thus actually marked for invasion by Japan with plans sitting up there on the shelf, but it conveys the essence of United States thinking of that possibility back in early 1942.

The Japanese landed on Tulagi in May to build a seaplane base, and in late June on Guadalcanal to build an airfield, threats to all of the Allied area and ships within range of land -based aircraft, constituting the initial rational for not letting Guadalcanal remain in Japanese hands. On August 7, 1942 the United States launched the First Offensive of the Pacific War with the landings of the U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal, their first objective to seize the landing strip they would rename Henderson Field.

The struggle for Guadalcanal became the great testing ground for the American will to prevail against the Japanese in the Pacific War. The threat to Australia, both perceived and real, was no doubt soon diminished by the overwhelming presence of American warships ships flooding into the Pacific by year’s end; and in the island-hopping campaigns which followed, the airfield on Guadalcanal became of less importance, but that does not diminish the reality that prevailed in the summer and fall of 1942.

Japan had, as already noted, in late June of 1942 landed at Guadalcanal and had set up its airfield, even though Japan, apparently, had earlier in that same month made a major adjustment in its thinking as to its immediate future plans. Up to June 11, 1942, Japan, according to historical documents quoted in other secondary sources, was known to have had plans to seize New Caledonia, the Fijis, and Samoa, to add them to her holdings and to cut off communications with Australia and New Zealand. However, as the historical record indicates, after the disasters in the Coral Sea and at Midway Japan is said to have put those plans back on the shelf because of her loss of 4 aircraft carriers and 400 ship and land-based aircraft and the experienced pilots who flew them, and Japan’s industry unable to keep up with making replacements. However, just how much of that was then actually known, and its significance assessed, by U.S. strategists in August is something to wonder about, and if it made any difference as to what Japan might do if they were permitted to retain their airfield on Guadalcanal.

What was known was that Japan had constructed an airfield on Guadalcanal, had a seaplane base at Tulagi, and was expanding its holdings into what presumably would be a giant staging area, an obvious stepping stone she could use in her attacks against Allied bases in the Pacific, and, against Australia. [In that regard, it was also said by the Dutch that their sacrifices in the Dutch East Indies had saved Australia from invasion. But, evidently all of the later after-the-war assessments by the U.S., with Japan’s cooperation, seem to confirm that Japan had no actual plans for invasion of Australia, but that little gem of information, including of course, General Griffith’s find of 1963, as stated above, was something the U.S. was not privy to in 1942.]

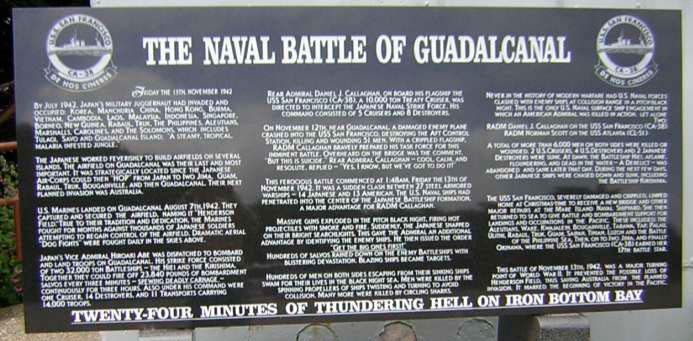

Plaque # 2, USS San Francisco Monument at Lands End. In the second paragraph:

"The Japanese worked feverishly to build airfields on several islands . . . . from Japan to Iwo Jima, Guam, Rabaul, . . .and then Guadalcanal, their next planned invasion was Australia."

Historians Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen, authors of World War II: The Encyclopedia of the War Years 1941- 1945, Random House, 1991, on page 357, in their short account of Guadalcanal they have this to say:

"The Guadalcanal field was a key to the Japanese plan to take Port Moresby at the southern end of New Guinea, paving the way for air strikes and a possible landing in Australia." [italics added]

As it turned out, after Midway, Guadalcanal was the next great proving ground as to who would prevail in the Pacific, and had Japan been successful nobody knows what the next move of the Japanese might have been.

move of the Japanese might have been. Yes, Japan had suffered the loss of 4 fleet aircraft carriers, but by mid-November Japan’s navy was still a force far more powerful than we had in the Pacific.

Admiral Ghormley ordered Admiral Fletcher to keep his 3 carriers and 2 battleships below the 10th Parallel. [the 4th carrier, Saratoga, was on the picket line guarding the approaches to Hawaii, when on 31 August it was damaged by a torpedo hit].

Assistant Secretary Forrestal in early September visited Ghormley in Noumea to assess the critical situation at Guadalcanal. Ghormley had a message from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to turn over to General MacArthur a regiment of ―experienced troops‖ and the transports required for their movement to Australia. Admiral Turner, who had also flown in to Noumea from his Espiritu Santo headquarters to confer on the crisis, could with Ghormley wonder if the Joint Chief message meant that Washington was actually saying to withdraw and turn over to MacArthur the Marine forces now on Guadalcanal. He could also wonder if the message wasn’t the Joint Chiefs’ way of saying that the 7th Marines and the 5th Defense Battalion, who were at that time aboard transports and slowly moving toward the New Hebrides from Samoa should be released to MacArthur.

Turner advised Ghormley of the impracticality of withdrawing any of the Marines from Guadalcanal and urged Ghormley to commit the 7th Marines and the 5th Defense Battalion to reinforcing Guadalcanal. [for that exchange see Brig.Gen. Samuel B. Griffith, USMC, The Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 110]. In the upheaval, the Guadalcanal marines remained there, the reinforcements were delivered; but the focus in that crisis clearly was on the protection of Australia, and if need be to assure that protection then, in the minds of the Joint Chief of Staff, Guadalcanal may have to be evacuated.

Turner, it will be remembered, then flew in to Guadalcanal to converse with Marine General Vandegrift on 12 September; and with Vandegrift vowed that Guadalcanal would be held.

On 15 September the Wasp [in which taskforce the San Francisco as Admiral Scott’s flagship sailed] was sunk by a torpedo.

Yet to come was the replacement on 18 October of Admiral Ghormley by Admiral Halsey; and on 26 October the loss of the Hornet, as the struggle for control of Guadalcanal and that airfield went on.

Thus by November the United States had also lost 4 of her fleet aircraft carriers in the Pacific, to equal the score card of the Japanese losses in the Coral Sea and at Midway. (Lexington in the Coral Sea, Yorktown at Midway, Wasp by a submarine on 15 Sept., and Hornet on 26 Oct.] and only 2 were left, both of them damaged [ Enterprise and Saratoga] and only 2 battleships [ Washington and South Dakota ] In all of that Pacific Ocean beyond New Caledonia there were no U.S. aircraft carriers or battleships until one of those two carriers and the two battleships were rushed to the Guadalcanal scene, but too late to join the ―Big Battle‖ of Friday the 13th of November of 1942, they did wreck havoc against another Japanese warship force in another night naval battle two nights later.

In February 1943 after the Japanese failure at Guadalcanal and evacuating the island did Japan give up on her grandiose plans for that part of the world? It does appear that after Guadalcanal Japan’s objective was to just do her best to hold on to what she had, but even that is open to question. The American Navy had to wonder about that for yet awhile; and in Edwin P. Hoyt’s , The Glory of the Solomons, published in 1983, on page 21, we read:

"The Japanese buildup for the attack on Australia and New Guinea continued [after the evacuation of Guadalcanal in February 1943]. Admiral Yamamoto had moved his advance bases back to Kolombangara and New Georgia Islands, which were then to be prepared, under the Japanese plans, to provide the same sort of bases that had been envisaged for Guadalcanal, staging points for air attacks on Northern Australia and the trade routes that brought supplies from America to General Douglas MacArthur’s forces in Australia. . . . .The movement against Australia was to make sure that MacArthur would be unable to carry out that promise [of returning to the Philippines]." [italics added]

After the Guadalcanal Campaign Japan had a lot more to be thinking about.

Heber A. Holbrook